The real value of the US money supply

Among investors and financial commentators we see continued controversy over the Fed's current loose monetary policy of active quantitative easing. My previous post covered the financial sector deflation I see as driving the Fed's actions, which many participants in that debate seem to have missed or to be unaware has been happening. Here I want to examine the question whether the Fed adding money has simply goosed prices in response as so many claimed on theoretical grounds must be the result, or whether it has actually added value. Theory and ideology leads many participants in the debate over policy to expect that all additions to the money supply merely transfer real purchasing power from some actors to others. They then frequently indulge in extreme rhetoric against that supposedly automatic result. There is a strong belief among these observers that increasing the money supply can never actually add value, that instead it merely devalues existing money claims.

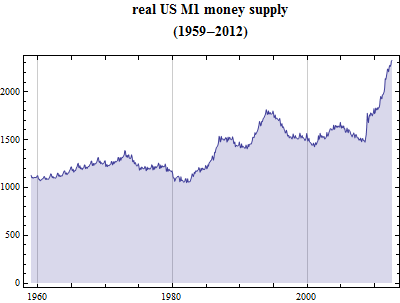

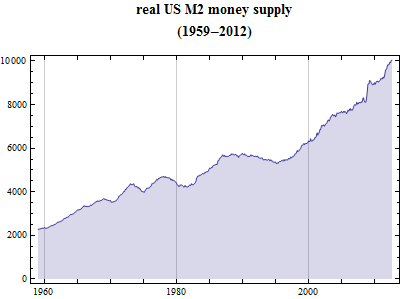

I consider the theoretical case for those propositions to be much weaker than is generally believed. And empirically I think they are demonstrably false. In this post I want to present some of the evidence for my position, from both empirical time series and theoretical argument. I begin with the bare facts, in the form of 2 time series showing the inflation adjusted purchasing power of the US money supply, measured by M1 and by M2. The inflation adjustment is done by the CPI for all urban consumers, with everything turned into current dollars. Here are the resulting charts -

The first thing to notice is just that the series are increasing and steadily so, particularly the broader M2 measure. This should be completely unsurprising - there is real economic growth, the real value of all assets in the US increases continually. Money is a small subset of those assets, but grows in real purchasing power along with everything else. Over the full period 1959 to now, the average growth rate of raw unadjusted M2 is 7.4% per year, of which only 4.5% is price inflation and 2.8% is real growth in total value. For M1 the raw growth rate is slower, only 6%, with 1.4% real value growth and the rest price change.

The high portion of the total increase that reflects price changes partly justifies the common intuition that increasing the supply of money increases prices -and other things being equal, it certainly does. The underlying monetarist point that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon has a sound basis. But the further, naive monetarist belief that all changes in money supply cause equal and opposite declines in the purchasing power of the monetary unit, is false. The higher quantity of dollars outstanding today compared to 1960 would purchase more in real value, not the same amount of real value. Each dollar exchanges for less, check, that is ongoing inflation. But the total does not exchange for the same amount, it exchanges for more. In the case of broader money including the savings forms in M2, a lot more. The total change in real M1 is more than a factor of 2, and of M2 more than a factor of 4.

It is also worth noticing that M2 grows considerably faster than M1, and the ratio of M2 to M1 has more than doubled, itself. Less of the total value of all assets in the society are in the form of narrow money than in the past. Greater efficiency of money substitutes and clearing "support" more broad money and more total credit per unit of narrow money base. Moreover, the rate of growth of M2 is in line with total GDP and the value of all dollar assets, as measured by the top line of the household sector balance sheet in the Z.1 "flow of funds" dataset. But the growth rate of M1 is considerably less than that overall growth rate, slower by about 1.4% per year.

The next important thing to notice about the series and especially the top, real M1 series, are the departures from trend and the changing direction of the series for some subperiods. For example, there is a real peak in December 1972 followed by a downtrend with its minimum in February of 1982. Over this period, the real value of M1 money supply fell by 24%, a decline of 3% per year. Prices were galloping along faster than narrow money. In my analysis, this reflects a declining real demand for money. In the following period, from that 1982 low to late 1993, the real value of the M1 money supply rose 73%, an increase of 4.7% per year. Prices were increasing in this period but modestly, at considerably slower rates than in the previous inflation. Narrow money grew much more rapidly than prices. Demand for money was increasing. This reflects a dramatic reversal in inflation expectations. Most investors are very familiar with that Volcker Fed success story, but many may not realize just how much narrow money supply grew over this period - without goosing prices.

The next period to notice is that from March 2006 to August 2008. In this period the Fed was standing on the brake, keeping M1 nearly flat while increasing short rates. The real value of the narrow money supply fell by 8.3% over this stretch, a decline of 3.5% per year. Then the emergency actions of the Fed in late 2008 push real narrow money sharply higher, with both M1 increasing and prices briefly falling outright. The real value of M1 jumps by 20.5% in the space of 4 months. And it has gone on increasing since, farther overall though not as sharply as that short period.

Now a theoretical point, one that seems so counterintuitive to monetarists that I expect its truth will be resisted stubbornly, but that I believe is justified by both the empirical data and sound theory. When the real value of the money supply increases from monetary expansion, real wealth can be and is being printed into existence by fiat. Not a mere reallocation from one holder to another. Not a mere pricing change or monetary illusion effect, but real value added.

Why do I say that sound theory supports this conclusion, when so many textbooks and monetarist tracts, thinking of the 1970s case and others like it, assert the opposite as a supposedly necessary theoretical proposition? I answer that I am merely applying econ 101 - the revenue maximizing point on intersecting supply and demand curves may occur at a higher quantity and lower price per item - down and to the right on the usual crossing curves - and is always the result of two forces, one of them the demand curve, and not just one, the supplied quantity. When demand for anything shifts to the right, the clearing price of that item would change upward if the quantity did not move. But the quantity moving to the right instead, may very well produce a higher product for price times quantity, or total value.

In my analysis, that is what happened on the financial crisis. The demand for money including for narrow money specifically, jumped sharply. Every sell order for every kind of risk asset was a buy order for money. The Fed met this panic safety demand by supplying the demanded item in much higher quantity, and the total value of that supplied quantity was sharply higher than previously. If they had not moved its quantity, its value would still have increased on the higher demand, in the form of higher exchange value for money, lower prices for everything else, aka a falling broad price level. But it likely increased by more, by letting its quantity move to meet the higher demand, instead.

Some reasons monetarist theory might not expect this result, are too glib "other things being equal" handwaving, that effectively assumes that the demand for money is a constant (which I believe the top graphic proves to a demonstration it is not), or the classical economics mistake of predicting something's exchange value from its *costs*. It is certainly true that the marginal cost of a new unit of fiat money is zero, and classical economists might expect that nothing with a zero marginal cost could add real value in anything like a general equilibrium. But in the age of software we ought to know better than that - the marginal cost of an additional copy of Microsoft Office is also essentially zero, but we all recognize it can and does have a positive exchange value. The prices picked for items with very low marginal cost are determined by demand and revenue maximization points, not by their marginal cost. In all such cases there are barriers to just anyone supplying more of the item at its marginal cost, to be sure. But it is a common experience that items with zero marginal cost but in demand, have positive exchange value and supplying more of those items can and does add total value.

So, one fundamental point - increasing the supply of money can and sometimes does simply print real value into existence. Men's demand for money is not directly inversely proportional to the quantity of it in existence. The demand curve for money is not a straight line, but curves, and also moves with time, as all other demand curves do.

Cases like the 1972 to 1982 period show that high inflation with increasing inflation expectations can result in a declining real money supply, as prices increase faster than money, demand to hold money falls, and the incentives needed to convince men to hold nominal assets get harder to meet, in the form of higher interest rates and similar. Monetary policy can be too loose, and in such periods it is too loose, and the monetarists are right about the corrective needed in such cases. But that is not the only case that happens. When demand for money is high and increasing, it is possible to create real value by meeting that demand, by letting people hold the asset they want. When the real value of the money supply is increasing, empirically, this is what is happening, not the 1970s inflation case.

As for the most naive monetarist expectation that the money supply "ought" to remain constant, and that any growth in the money supply simply moves value from some hands to others (unjustly, is the usual subtext), I think this analysis shows it is false empirically. Sometimes creating more money creates net value, and not just in nominal terms. It does so in the usual way, by accommodating a real demand to hold a specific item, in preference to other items. As such, as counterintuitive as it may seem, creating net new money can be a form of production that can and does add real value, as surely as moving goods from locations where they are in lower demand to others where they are wanted more urgently, adds value. Transportation does not create goods but it increases their value. Changing the form of financial claims does not increase the pool of real assets against which those claims run, but it still can increase their value, by accommodating the subjective asset preferences of all participants in the markets, more than an alternative.

I hope this is interesting, and questions or comments are welcome.

Disclosure: I have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.