Saudi Arabia's oil minister gained agreement at the OPEC meeting to combat the U.S. shale oil boom, arguing against cutting crude output in order to depress prices and undermine the profitability of North American producers. The Saudis are waging a market-share battle, according to a Reuters report ("Inside OPEC room, Naimi declares price war on U.S. shale oil," November 28, 2014).

The price war is on.

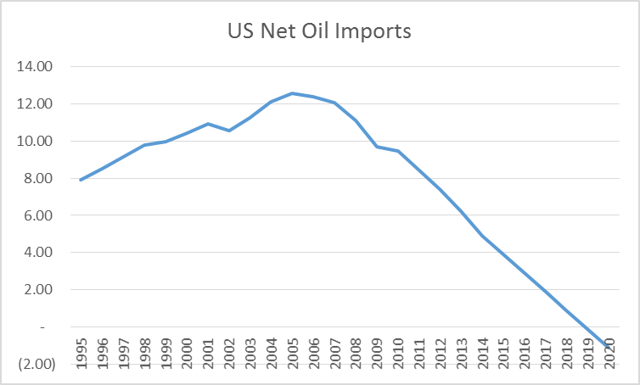

Given the new realities of the US oil market, imports will almost certainly average about 4 million barrels a day (mmbd) in 2015, down from their peak of 12 mmbd in the 2005-07 period (see Exhibit 1). And if recent trends continue, OPEC would be competing with North America as a net oil exporter by 2020.

Exhibit 1

Sources: Energy Information Administration, 1995-2015; Boslego Risk Services, 2016-2020.

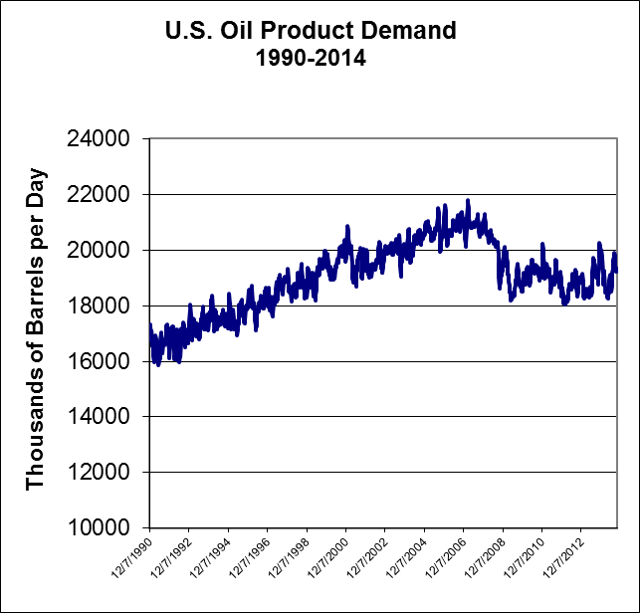

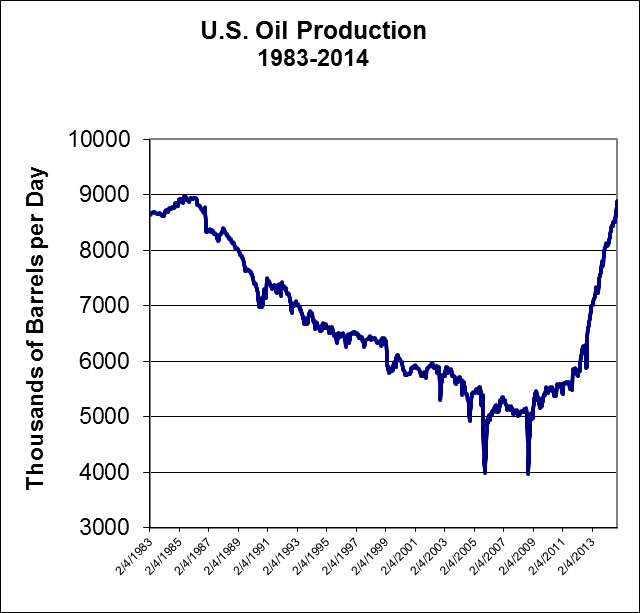

Behind the dramatic change in the import trend are three factors: production of crude and natural gas liquids and petroleum product demand. The increase in US oil production has been widely reported. To long-term oil market participants and observers, it's nothing short of miraculous (see Exhibit 2). What is not as well-known is that it explains only a little over half of the net displacement of oil imports since 2007.

Exhibit 2

Data Source: US Energy Information Administration, DOE.

In addition to the increase of crude oil, producers have increased production of natural gas liquids and renewables such as ethanol. These are feedstock to refineries that substitute for crude oil to make petroleum products, such as gasoline. That increase in the past 7 years is about 1.5 mmbd per day.

To contrast the size and speed of these gains in crude and NGL output, the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field on Alaska's North Slope began production in 1977 when the Alaskan pipeline was completed. Its production peaked 11 years later at 2 mmbd.

The third source of import displacement has been a reduction in consumption. U.S. demand for petroleum products peaked in 2007, notwithstanding the economic recovery following the financial crisis (see Exhibit 3). The drop in US consumption has since displaced another 1.7 mmbd of imports since October 2007.

Exhibit 3

Data Source: US Energy Information Administration, DOE.

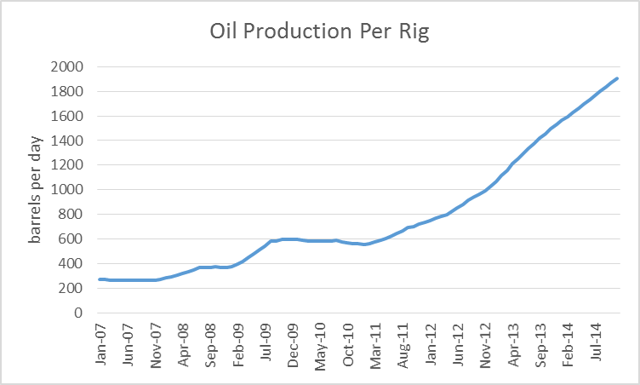

Finally, the Saudis cannot help but notice US drilling productivity gains. Oil production per rig, across the six shale play regions, is up 91% v. 2 years ago, on average, and rising (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4

Data Source: US Energy Information Administration, DOE.

Lessons of the 1980s

Saudi Arabia came to the conclusion that it had to do battle now. It has competed for market share before, after its sales had dropped to extremely low levels.

The Iranian revolution in 1979 was followed by the Iran-Iraq war in 1980. Both events, and other developments, reduced OPEC oil output by about one-third from 1979 to 1981.

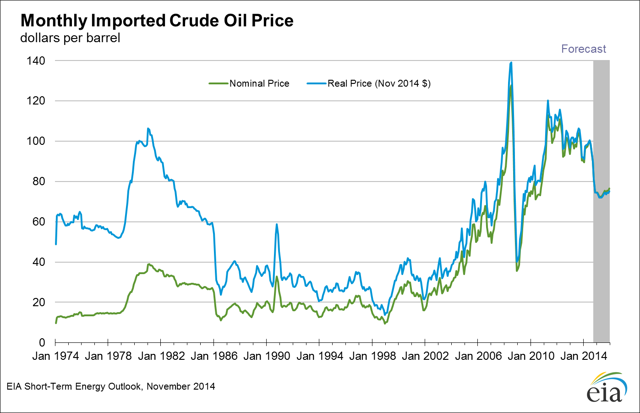

That supply shock sent prices through the roof, more than doubling to over $40 per barrel. For perspective, the 1981 price peak was the equivalent of $106 in today's dollars (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5

Inflation soared to 13.5% in 1980 and the prime interest rate peaked at 21.5%. The US economy was more oil-dependent then in its need to generate GDP, and so a severe economic recession began in July 1981. These developments--higher prices and a recession--reduced the demand for OPEC oil. Rather than let oil prices adjust accordingly, OPEC members tried to charge high prices by making production cuts.

The real price of oil nonetheless eroded by 40% from its peak in 1981 through October 1985. The 'call' on OPEC oil in 1985 was less than half of its 1979 rate.

In November 1985, Saudi Arabia decided it would no longer act as the 'swing' producer, absorbing much of the loss in production. Saudi production had plummeted from almost 10 mmbd in 1979 to just 2 mmbd in 1985.

Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani responded with a policy of unrestrained OPEC oil production, which caused a rapid drop in oil prices and a budget crisis at home. In nominal terms, the price plunged from $32/b in November 1985 to below $10/b in July 1986.

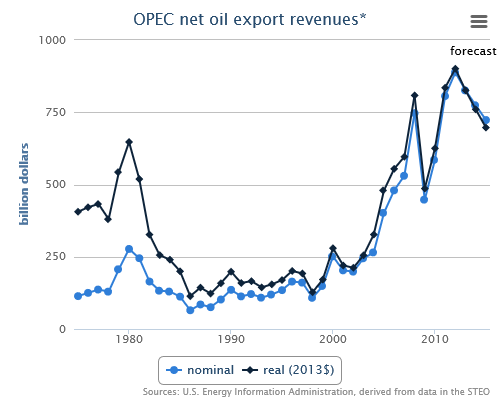

The price collapse damaged OPEC and US producers and their economies. OPEC revenues remained depressed for the 12 following years, except during the Gulf war, leading to Saudi budget deficits that left the country deeply in debt (see Exhibit 6). Unemployment in Oklahoma and Texas rose to about 9%.

Exhibit 6

In the final analysis, the low price strategy did achieve the goal of restoring Saudi sales, eventually, at much higher prices. But that took two decades.

Futures Markets and Hedging

In a price war, the real ammunition is barrels. The fundamentals of 2014 are not the same as they were in 1985. Then, the Saudis had about 10 mmbd of spare production capacity. Now, there may be only 2 mmbd excess capacity in all of OPEC. Still, that is enough to drive prices lower.

Saudi Arabia and OPEC are not in control of the oil market today. The oil futures market is.

With many oil shale producers hedged, they can withstand a drop in prices and still continue their drilling programs. If a producer is hedged at $60 and the cash market is priced at $30, the producer receives the $30 from cash market and another $30 from the futures hedge.

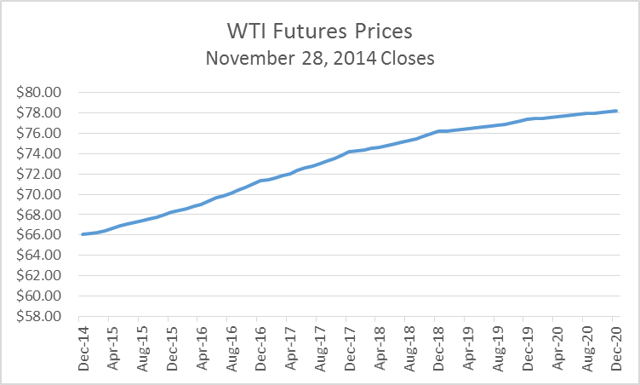

Even after the plunge on Friday, oil futures markets still offer relatively high price levels that can ensure the profitability of drilling projects for many years to come (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7

On the other hand, those who are not hedged are likely to be punished. In early November, Harold Hamm, chairman of Continental Resources (CLR), "America's Oil Champion," and king of the Bakken oil shale plays, reportedly closed their hedges, "allowing us to participate in what we anticipate will be an oil price recovery." On Friday, November 28, 2014, CLR suffered a 20% loss in a single trading session.

Analysts are busy assessing production costs in oil shale plays to determine a bottom to oil prices. But commodity futures prices can and do fall well below production costs. Oil futures hedging implies that prices must fall sharply and remain below production costs for a long period.