By Alberto J. Boquin, CFA

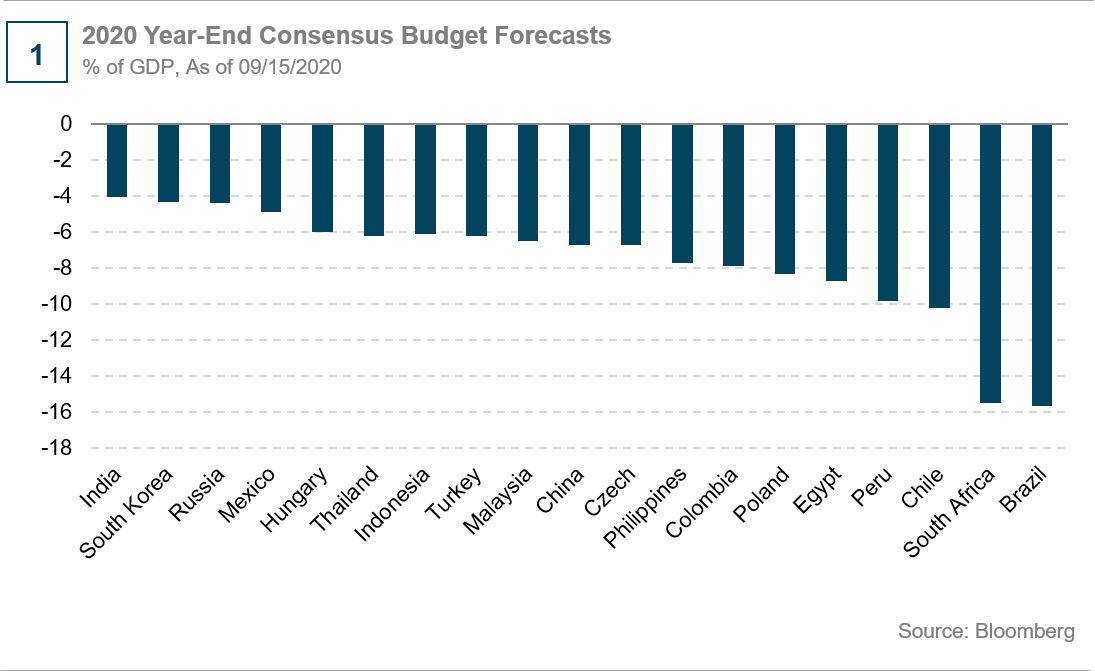

Countries around the world have responded to the economic downturn by implementing fiscal stimulus. This intervention has led to a deterioration of fiscal finances everywhere. However, even by these relative standards, Brazil and South Africa look particularly dismal. Both countries are running fiscal deficits in the mid-teens (see Chart 1). Debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in both countries is approaching 90%. Growth prospects are also quite bleak, which should push debt loads for these BB-rated sovereigns even higher over time.

Politicians need to make some tough choices in the years ahead. The only silver lining is that both countries can muddle through for some time still. Their debt stock is mostly denominated in local currency, external debt is termed out, and the domestic banking systems are well capitalized and liquid.

The debt mix enables these countries to use their currencies to weaken and act as a rebalancing lever for the economy. In South Africa, only 12% of the debt is in hard currency, and the next large external debt maturity is not until May 2022 when $1 billion of principal is due. In Brazil's case, less than 4% of the debt is in foreign currency. One risk for Brazil is its reliance on floating-rate debt, which allowed the country to reduce the weighted-average cost of debt to 7% currently, down from 14% in late 2015. However, in an eventual rate-hike cycle, the risks of this debt could be significant.

Since their downgrade to high yield, Brazil and South Africa have become less attractive to foreigners that often have credit rating constraints. Luckily for both countries, the domestic banking systems remain very liquid and willing to finance the sovereign. In Brazil, private-owned banks have found few attractive lending opportunities amid a recession. As loans mature, they have reinvested that cash in sovereign bonds. Bank holdings