Let's Start

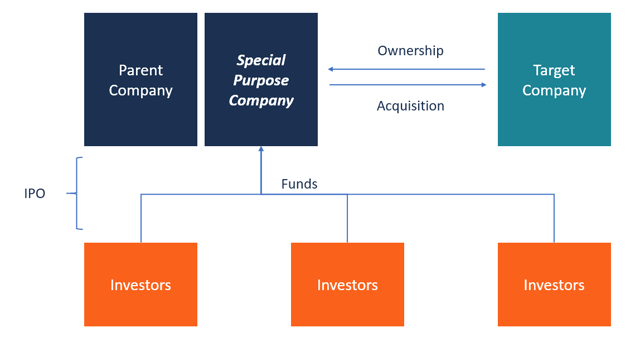

Startups are now more than ever taking their companies public through special purpose acquisition companies (“SPACs”). SPACs do not take part in commercial operations and are commonly known as “shell companies.” These companies are designed to raise enough money to discover a target company and secure a reverse merger. After funds are raised, the SPAC must complete an acquisition (via a reverse merger in which a public company, in this case, the SPAC, acquires a private company) within two years, or the money raised will go back to its investors. This system allows the private company to avoid the drawn-out and complicated process of going public autonomously.

Many companies are noticing and taking advantage of the benefits associated with selling to a SPAC. Compared to a typical private equity deal, a company sold to a SPAC may retain an increase in the sale price of up to 20%. Furthermore, companies may avoid the lengthy process of an initial public offering (“IPO”) if acquired by a SPAC. Essentially, SPACs offer business owners a faster IPO process with experienced partners and officers within the SPAC guiding the operation.

With $4B raised, the largest Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) ever, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings Ltd, started trading on July 22, 2020. Having a shaky reputation historically, SPACs are becoming more popular than ever as they help private companies go public faster and easier. Additionally, SPACs provide greater certainty of access to public capital, which is particularly valuable during today’s highly volatile economic environment.

These are my takes as an investment advisor and who helped companies to sell secondaries shares before an IPO and currently as a VC investor with portfolio companies going through both SPAC and traditional IPO processes. The purpose of this post is to help demystify the process, as SPACs are clearly proliferating and may play a key role in the near term.

SPAC IPOs have seen resurgent interest since 2014, with increasing amounts of capital flowing into the concept:

- 2014: $1.8bn across 12 SPAC IPOs

- 2015: $3.9bn across 20 SPAC IPOs

- 2016: $3.5bn across 13 SPAC IPOs

- 2017: $10.1bn across 34 SPAC IPOs

- 2018: $10.7bn across 46 SPAC IPOs

- 2019: $13.6bn across 59 SPAC IPOs

The first of all

What is a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC)?

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a corporation formed for the sole purpose of raising investment capital through an initial public offering (IPO). Such a business structure allows investors to contribute money towards a fund, which is then used to acquire one or more unspecified businesses to be identified after the IPO. When the SPAC raises the required funds through an IPO, the money is held in a trust until a predetermined period elapses or the desired acquisition is made. In the event that the planned acquisition is not made or legal formalities are still pending, the SPAC is required to return the funds to the investors, after deducting bank and broker fees.

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a corporation formed for the sole purpose of raising investment capital through an initial public offering (IPO). Such a business structure allows investors to contribute money towards a fund, which is then used to acquire one or more unspecified businesses to be identified after the IPO. When the SPAC raises the required funds through an IPO, the money is held in a trust until a predetermined period elapses or the desired acquisition is made. In the event that the planned acquisition is not made or legal formalities are still pending, the SPAC is required to return the funds to the investors, after deducting bank and broker fees.

How Does a Special Purpose Acquisition Company Work?

Founders

A special purpose acquisition company is formed by experienced business executives who are confident that their reputation and experience will help them identify a profitable company to acquire. Since the SPAC is only a shell company, the founders become the selling point when sourcing funds from investors.

The founders provide the starting capital for the company and they stand to benefit from a sizeable stake in the acquired company. The founders often hold an interest in a specific industry when starting a special purpose acquisition company.

Issuing the IPO

When issuing the IPO, the management team of the SPAC contracts an investment bank to handle the IPO. The investment bank and the management team of the company agree on a fee to be charged for the service, usually about 10% of the IPO proceeds. The securities sold during an IPO are offered at a unit price, which represents one or more shares of common stock.

The prospectus of the SPAC mainly focuses on the sponsors, and less on company history and revenues since the SPAC lacks performance history or revenue reports. All proceeds from the IPO are held in a trust account until a private company is identified as an acquisition target.

Acquiring a Target Company

After the SPAC has raised the required capital through an IPO, the management team has 18 to 24 months to identify a target and complete the acquisition. The period may vary depending on the company and industry. The fair market value of the target company must be 80% or more of the SPAC’s trust assets.

Once acquired, the founders will profit from their stake in the new company, usually 20% of the common stock, while the investors receive an equity interest according to their capital contribution.

In the event that the predetermined period lapses before an acquisition is completed, the SPAC is dissolved, and the IPO proceeds held in the trust account are returned to the investors. When running the SPAC, the management team is not allowed to collect salaries until the deal is completed.

SPAC Capital Structure

Public Units

A SPAC floats an IPO to raise the required capital to complete an acquisition of a private company. The capital is sourced from retail and institutional investors, and 100% of the money raised in the IPO is held in a trust account. In return for the capital, investors get to own units, with each unit comprising a share of common stock and a warrant to purchase more stock at a later date.

The purchase price per unit of the securities is usually $10.00. After the IPO, the units become separable into shares of common stock and warrants, which can be traded in the public market. The purpose of the warrant is to provide investors with additional compensation for investing in the SPAC.

Founder Shares

The founders of the SPAC will purchase founder shares at the onset of the SPAC registration, and pay nominal consideration for the number of shares that results in a 20% ownership stake in the outstanding shares after the completion of the IPO. The shares are intended to compensate the management team, who are not allowed to receive any salary or commission from the company until an acquisition transaction is completed.

Warrants

The units sold to the public comprise a fraction of a warrant, which allows the investors to purchase a whole share of common stock. Depending on the bank issuing the IPO and the size of the SPAC, one warrant may be excisable for a fraction of a share (either half, one-third or two-thirds) or a full share of stock.

For example, if a price per unit in the IPO is $10, the warrant may be exercisable at $11.50 per share. The warrants become exercisable either 30 days after the De-SPAC transaction or twelve months after the SPAC IPO.

The public warrants are cash-settled, meaning that the investor must pay the full cost of the warrant in cash to receive a full share of stock. Founder warrants, on the other hand, may be net settled, meaning that they are not required to deliver cash to receive a full share of stock. Instead, they are issued shares of stock with a fair market value equal to the difference between the stock trading price and the warrant strike price.

Some numbers

Growing over time, SPACs have accounted for 33% of US IPO filings during the first half of 2020. Please note that the chart above doesn’t even include the $4B SPAC -Pershing Square Tontine Holdings Ltd, which went public late July. While writing this post, we are hearing that Dragoneer is the next to raise their own SPAC. Given the environment, it would be fair to expect many late stage investors to do the same soon.

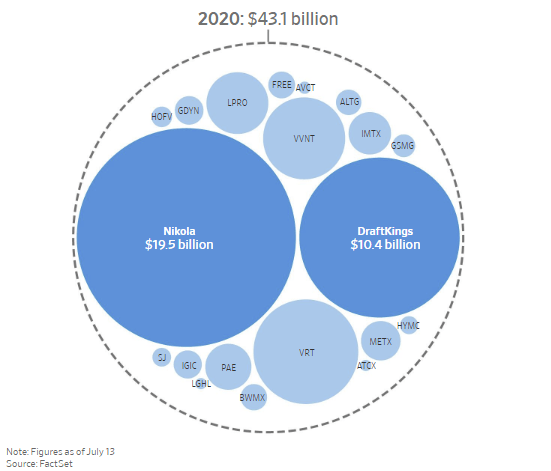

Recent successful transactions played a key role attracting more interest in SPACs. Below are market capitalization of companies that have gone public via SPAC deals in 2020, by WallStreetJournal.

How can a private company go public via SPAC?

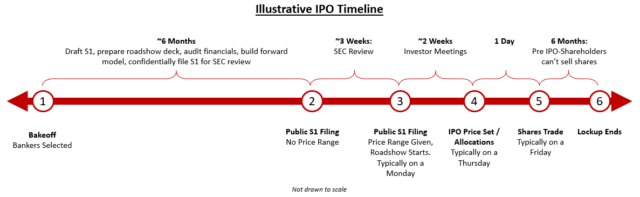

First, in case you are not familiar, I’d highly recommend taking a look at the traditional IPO process, which is illustrated below and described with details in this great post.

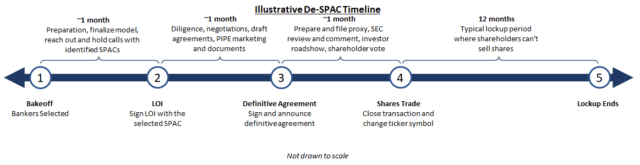

A private company can go public via SPAC in a matter of a few months, compared to 6+ months of traditional IPO preparation process. Here is how the “De-SPAC process” works:

- Step 1 — The Bakeoff: Once a company decides to go public, the first thing to do is reaching out to a select group of investment banks. As SPACs are becoming more mainstream, more and more bulge brackets are getting into the space. During the “bakeoff” (aka “beauty contest”), each bank would pitch why they would be best positioned to help the company in the process. The company will then select their top investment bank, based on team, track record, and industry knowledge, among others. With the help of the bank, the company would finalize investor deck & financial model, start reaching out to relevant SPACs and holding calls with them. The goal is receiving letter of intents and the negotiations start.

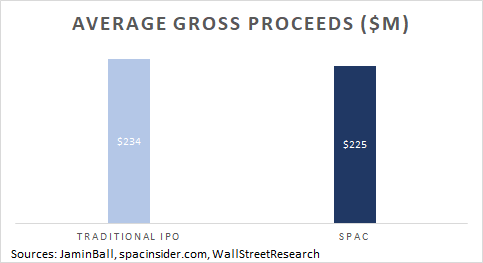

- Step 2 — Letter of Intent: Once the Letter of Intent (LOI) is signed, the post-LOI diligence process kicks off. Simultaneously, teams start drafting definitive agreements, building PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) marketing documentation and holding calls with potential PIPE investors, which are typically very large institutional investors. The target is signing a definitive agreement (possibly incl. PIPE commitments) and announcing the transaction. Here is what such an announcement looks like (Nikola). When we look at the recent historical figures, there is no material difference between the amount of gross proceeds raised via SPAC and traditional IPO (see the chart below), SPACs allow tapping into significantly large pools of capital, thanks to the engagement with PIPEs. This would help a company raise additional hundreds of millions of dollars (PIPEs could be as large as 2–3X of SPAC proceeds). Moreover, unlike traditional IPO, a company would know the exact price and the total amount of money raised much earlier in the process.

- Step 3 — Definitive Agreement: Once the proxy is filed, SEC review and comment period starts. Simultaneously, investor roadshows and analyst day would take place. To approve the De-SPAC process, a shareholder vote (Remember that SPAC shares are already publicly trading) needs to be called. The merger transaction needs to get an affirmative vote from 37.5% of the public shares and the 20% Sponsor Shares (50% shareholder vote). Once the merger is approved, the SPAC and the company combine into a publicly traded operating company, which now has the SPAC and PIPE cash on its balance sheet. Finally the ticker gets changed and the closing of the business combination is announced, just like Nikola did here.

- Step 4 — Lockups & Trade: Lockup refers to the time period where existing non-public shares can’t be traded after IPO. For De-SPACs, there is typically a 12-month lockup (vs. 6-month lockup via traditional IPO) period where shareholders can’t sell any shares. During this time, an important component to watch is the warrants of the SPAC entity. The warrants could have substantial pricing pressure on the newly trading company. Matt Levine of Bloomberg lays out the basic math behind it by using the Nikola example as follows:

Here was a trade. Nikola Corp., the maybe-one-day-electric-truck-maker that went public via a blank-check merger last month, has a lot of warrants outstanding. Each warrant (ticker NKLAW) allows you to pay $11.50 to buy one share of Nikola common stock (ticker NKLA). The trade was:

- Buy one warrant for $24.62.

- Pay $11.50 to exercise the warrant and get a share of stock.

- Sell the stock for $48.84.

- You pay $24.62 + $11.50 = $36.12. You get $48.84. Your profit is $12.72. Pretty good, no?

- You can’t do this trade now. Those numbers are closing prices from Friday, back when the trade was good. The numbers are different now: The warrants closed yesterday at $27.10; the stock closed at $38.45. If you do the trade now you’ll lose 15 cents, never mind. Up until Friday you could do this trade and make a lot of money — Nikola shares got as high as $79.73 on June 9, when the warrants closed at $29.49, for a profit of $38.74 on this trade — but now you can’t. The gap has closed.

--------------------

Conclusion

One final caveat is that most of the terms mentioned are negotiable, which can be seen as a benefit of SPACs, the flexibility of deal structuring. On the flip side, because terms can be negotiated broadly, this shows the importance of having expertise on your side. Given the current activities in the market, I expect SPAC gross proceeds to surpass traditional IPO proceeds this year.

About the Author

Mr. Koch — a serial entrepreneur and late-stage investor specializing in secondary shares.

Previously: Twilio, Xiaomi, iQiyi, Tilray, Livongo, Bandwidth.

Currently: Robinhood, Grab, Toss, Coursera, Epic Games, Chime, and other companies.

Contact — here, If you are a startup building in this space — email or DM me to be included in this article.

—

The content was collected from various open sources (including content from the blog by Baris Guzel) and does not provide any one-stop recommendation for the purchase of shares via SPAC. All data was used for only informational purposes and does not contain insider information that may be malicious or refuted by the company and SEC.

This communication does not represent an offer or solicitation to buy or sell securities. Such an offer must be made via definitive legal documentation by the buyer or seller of securities, please check the SEC rules before buying shares from any stock-suppliers.